The Turkish sport of cirit

During our travels in Middle East countries, my wife, Moreen, and I have seen the horse valued as a treasured necessity for both transportation and animal husbandry. Yet, as in Western countries, we’ve also seen horses used for sports, though most of the games are quite different from the ones we view.

You may have seen on TV scenes of an Afghanistan horseman riding wildly in a cloud of dust chasing another horseman carrying a sheep’s or goat’s head; buzkashee is Afghanistan’s national game. Eastern Turkey also has a sport where men ride horses at breakneck speeds; however, their game appears to have specific rules with an umpire and other officials. The name of this exciting spectator sport is cirit.

Several years ago, while traveling with a tour company that has since retired, we spent two days in Erzurum, Turkey. Erzurum is certainly more developed than most cities in eastern Turkey, though it too experiences the ravages of the area’s harsh winters. I’ve always wondered how locals stay reasonably warm in some of the city’s old homes seen scattered among more modern buildings.

Erzurum benefits by having Turkey’s only university in the country’s eastern section, which translates into the city’s having a fairly nice museum and a 2-star hotel (Oral Hotel) close to the campus. Additionally, Erzurum has several interesting ancient structures, some nearly 1,000 years old, my favorite being the Cifte Minare Madrasa (Twin Minaret Madrasa). However, my memories of Erzurum focus on a special cirit practice session we were fortunate to attend between two local competing teams.

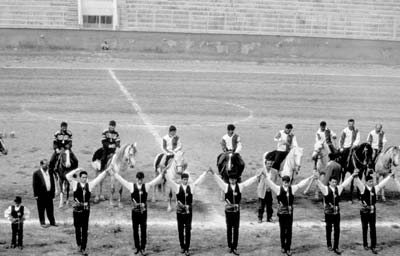

Erzurum’s cirit stadium

From what I understand, Erzurum has the only stadium built especially for cirit. It is constructed of concrete, with about 20 rows of seats on both sides of an extended rectangle approximately the width of but somewhat longer than one of our football fields. Both ends of the stadium are slightly rounded and open. Here, a team of seven to 10 horsemen await the challenge from a team at the opposite end.

As in many of our sporting events, the two teams first line up in front of the spectators and an umpire or local leader introduces the players (horsemen). As I don’t speak Turkish, I can only assume the official also reviews the rules of cirit, which seem fairly straightforward.

A rider from one team approaches the other at a full gallop before throwing a wooden spear (about the size of a broom handle) into the ground right in front of the opposition, as if he is laying down a gauntlet. The lone rider then hightails it back to his end of the open stadium as fast as his horse can run.

Usually two members, but sometimes only one member, of the opposite team take after the lone rider also at full speed. The team throwing the spear gets a point if the rider safely returns to his end of the stadium without being captured. If captured, the challenged team is awarded a point.

To capture a rider, the challenged team must either get ahead of the lone rider or throw his spear in such a way that the umpire believes the spear could have hit the rider. It appears, or at least it seemed so in this practice session, the object is not to actually hit the rider. Also, a challenged rider is penalized if his spear strikes the lone rider’s horse.

Special points are awarded if the lone rider is able to catch the thrown spear in midair while fleeing back to his end of the stadium. It requires great skill to ride at full speed, hold the horse’s reins with one hand and use the other to catch the thrown spear.

The game we witnessed lasted for over an hour. It was divided into two halves, with a halftime break for the horses and riders. We were very impressed with the horsemanship and with the stamina of the horses.

Since this was a practice session scheduled for a group of tourists, the stands were nearly empty, but the few locals sitting next to us let us know by yells of encouragement when they saw a great ride. Similar to the locals, we too quickly chose a favorite: the rider with a full, snow-white beard who easily was the oldest of the group. He probably lost more points than he won, due to his horse or, heaven forbid, his age, yet we cheered him on each of his rides. He maintained a stoic expression but occasionally sneaked a look at us, likely embarrassed by our cheers of encouragement.

After the game, we walked among the riders and their mounts as the umpire announced the score and winner. Our favorite rider’s team lost, but, again, don’t most Americans root for the underdog, especially in baseball (ex., Chicago Cubs)?

Minutiae

Dianna Darke’s book “Discovery Guide to Eastern Turkey and the Black Sea Coast” has a detailed section about Erzurum and the surrounding area. My copy was published by Michael Haag, Ltd. (P.O. Box 369 London NW3 4DP, England), but it is also put out by Immel Publishing (20 Berkeley St., Berkeley Square, London W1X 5AE. ISBN 0902743740 — 352 pp., $79).

Action photos of the horsemen were taken using ASA 400 slide film with a 200mm lens normally braced on a stadium handrail. On some, I “panned” the camera, i.e., continually focused the camera on the rider while moving the camera to match the horse’s movement.

As always, those of you traveling to countries discussed in this column should use common sense, especially in these tense times.