Mali and Burkina Faso with ElderTreks

I’m home again, unbitten and unbowed, after 22 days in West Africa with ElderTreks (597 Markham St., Toronto, Ont. M6G 2L7, Canada; 800/741-7956 or www.eldertreks.com). Just getting there was arduous, with long flights and long layovers. There were only 12 in our group. Everything except tips and airfare was included in the price of $4,295. The tour took place Feb. 7-28, ’06.

We began in Bamako, the capital of Mali, a country twice the size of Texas, whose heart and soul is the mysterious 2,500-mile-long Niger River. In Bamako, we visited the world’s greatest recycling market, where anything plastic or metal is cut up, ground up or chopped up and made into nails, boats, clothes, mattocks, wheelbarrows — you name it — all without the benefit of electricity.

Djenné, a UNESCO World Heritage Site famous for its mud mosque, was our next stop. The mosque holds 3,000 worshipers and is the largest mud structure in the world. Each year at the beginning of the rainy season, which melts the exterior, 4,000 town residents assemble and, standing on stick supports, re-mud the exterior. The original mosque, built in the ninth century, was replaced by the present structure in 1907.

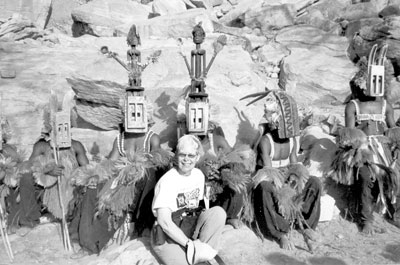

We visited the Dogon country and watched the tribal dancers. For the dance, they wear colorful and elaborate masks that represent ancestors, animals and totems. Some dancers teetered on 8-foot stilts while others shook shredded bark tassels and frills.

The Dogon villages sit at the base of the Bandiagara Escarpment. Originally, the first settlers, the Tellem, lived high up on the cliffs. They have disappeared, but their history lives on in mud granaries, tiny cave homes, broken pottery and colorful rock paintings. We had the privilege of hiking up to one of these old villages, and it was indeed a highlight of the trip.

We spent a night camping on the roof of the Dogon chief’s house and then headed for the Niger River, where we boarded our pinasse, or motorized riverboat. After three days of watching the vibrant life of the villages along the banks plus birding and spotting an occasional hippo, we arrived in the legendary city of Timbuktu, a dusty, windy, dry shadow of its former self but Timbuktu nonetheless.

A place everyone has heard of but few have seen, in its glory days Timbuktu (Tombouctou) was a center of Arab learning and commerce. At its peak, in 1550, 24,000 students studied in 150 madrassas, and great caravans of camels — weighed down by slabs of salt, as valuable as gold — arrived frequently. The salt caravans still appear, but it won’t be long before the city succumbs to the creeping sands of the Sahara Desert.

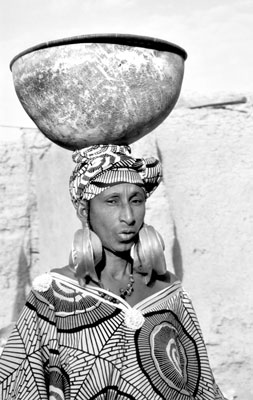

A day’s drive brought us to Mopti for a visit to one of the local markets. They are bustling, colorful places where, in addition to selling produce and goods, braiding hair, eating and napping (not to mention laughing at the dust-covered tourists), everyone visits and catches up on the latest news.

The border crossings were long and involved, and we added four new stamps to our passports as we left Mali and entered Burkina Faso.

Our first stop was Ouagadougou, a.k.a. Ouaga. There, we had an audience with the Moro-Naba, the king of the Mossi people. Wearing elaborate lime-green silk robes and a perky hat, he appeared to us in a magnificent carved ceremonial chair. In one hand he held a lion-headed wooden staff and in the other, a cell phone, which rang several times when we were there.

The next day we reached the painted-houses region of Burkina Faso. These mud-brick dwellings of the Gourounsi people have new stucco applied every year and then are repainted in geometric patterns of red, black and white. The people were hospitable, and in the evenings we joined the residents in dancing to the traditional music of the balafon, kora and drum. The sound traveled far into the night and brought many villagers from several miles away.

Four more stamps and we were back over the border and finally back to Bamako. We had driven almost 3,000 miles in 22 days, with only four flat tires and two overheated engines.

We had two excellent guides on this tour, one a Malian and the other, Canadian, as well as five drivers and a cook. The food ranged from pretty good to boring to terrific and in the middle of nowhere was generally the best available. Accommodations ranged from “best available” (where water and power could be iffy) to the 5-star Sofitel in Ouagadougou. We very quickly learned that air-conditioning is more important than running water and that camping isn’t for those who like their creature comforts.

This trip is certainly not for everyone. We spent many hours in the vehicles, stopped by the side of the road for bathroom breaks, eating endless picnic lunches under baobab trees and camping with few facilities. But to see what we saw, all of the above was necessary. It was a wonderful trip.

— ELLEN JACOBSON, Centennial, CO