Egypt's enchanting Siwa Oasis

by Roxana von Kraus, Boston, MA

“American? Welcome. Welcome to Egypt!”

My being the only foreigner at the Alexandria bus station, my passport received special attention, with all the data recorded carefully in a worn-out register. I was on my way to the ancient Siwa Oasis, located 600 kilometers west of Alexandria and about 62 from Libya. (It is actually so close to the border that the entire area is considered a military zone and all visitors on desert safari need a special travel permit.)

It might have been easier to reach Siwa by crossing the border from Libya, but I preferred to follow Alexander the Great’s journey from his city by the sea, Alexandria, to the oasis of Siwa — the route he took in 332 B.C. when he traveled to the renowned Oracle of Ammon (Amun).

Setting out

The West Delta bus was old and dusty though comfortably functional. A large “No smoking” sign was displayed at the entrance, but the driver finished up a pack of Cleopatras by the time we made it out of Alexandria. It was a 9-hour drive and he needed to be happy and alert; the cigarettes kept him satisfied, and very loud music ensured the vibrancy of the trip.

I wished I could understand Arabic. By the end of the trip it felt like I did.

We passed through deserted seaside resorts and towns with beautiful calligraphic names. I had no idea where I was, and after about six hours I dared the question, “Where are we?”

“Marsa Matrouh” was the answer. We had covered the entire coast and were leaving the sea for the desert. Heading south, we traveled along the desert route, finished in 1980, that put Siwa on the map — at least for the common traveler like me.

This route of 300 kilometers was covered by Alexander the Great in eight days. Our ride brought us to Siwa in three hours.

Introduction to the oasis

The oasis lies 18 meters below sea level, along the rim of the Great Sand Sea. Over the centuries, it was known by many names: Penta, as inscribed at the second-century-B.C. Edfu temple; Ammoneion, as it was known during the Roman era, and Al Waha al Agsa, its name in the 15th century, when it was inhabited by Berber tribes.

During the Late Pharaonic, Hellenistic and Roman periods, Siwa was well known as a religious and economic center. The camel caravans carrying salt, dates, ivory and gold across the desert to the Mediterranean made the oasis a commercial desert port.

Today, Siwa has about 20,000 inhabitants, although it seemed like far less while I was in town. There are only two main streets, with charming cafés, bookshops, restaurants and Internet access. There are also bike-rental and photo shops, plus “supermarkets” with organic foods, spices and the renowned Siwa dates.

There are about five hotels “downtown,” and farther out are desert camps, temples and hot spring baths.

The main type of transportation vehicle in town is a little white cart with a sleepy donkey. My young driver met me at the bus station.

“Welcome to Siwa. I am Mohamed and I will take you to Shali Lodge. Where are you from?”

I was impressed — even more so when he repeated the same greeting in French, Italian and German.

I was not the only foreigner in town. Even Egyptians coming from Cairo, Marsa Matrouh or Alexandria to live and work in Siwa are seen as outsiders by the locals. The local language, Siwi, is a Berber dialect spoken also in some areas of Maroc, Algiers and Libya.

Home away from home

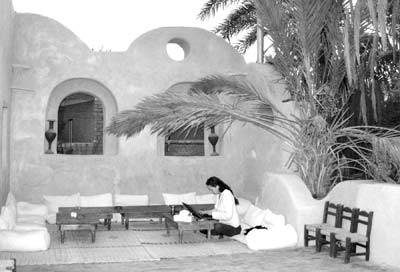

My hotel, Shali Lodge, was a jewel. Eight breezy rooms surrounded an inner court, with walls of sand bricks and large pots of blooming flowers.

Stone steps led to the roof, an open area covered with white cotton pillows, local carpets and copper pots. There I found Laura, an Italian journalist working on her laptop, and Ali, a charming Iraqi national who traveled through Siwa every year.

Present also is the Siwan working force: Mahmoud, a diver from Alexandria planning desert safaris; Mohamed and Mustafa, local policemen; Ashraf, who was building an environmentally friendly hotel, and Madame Hayat, who owns a desert camp. A British land developer joined our little entourage, and Katerina, a young woman from Ottawa, invited me to her dinner table.

It seems that Siwa is a place to get to know more through its people than through its landscape.

The other side of the hotel terrace holds 10 wooden tables, which make up Kenooz, “the best restaurant in town.” A large selection of exotic pizzas plus Arabic dishes served in steaming clay pots made this place home, for me.

Soon my daily routine was set. I started with a breakfast of omelets, falafel (perhaps the best in the country) and espresso ($5) downtown at Abdou. Most days I did not move from my café table, playing chess all morning, so lunch came naturally at the same place. Dinner at Kenooz by candlelight ($15) was followed by a visit to the garden restaurant next door, where Ali would serve lemongrass chai and play Italian music till 3 in the morning.

What to do?

Most of the time when you travel to a foreign place you move around, visiting nearby sites and cities. Not in Siwa. Here you come to stay.

The morning vibrancy of a bike ride to the surrounding temples dissolves into a perfect day of nonactivity by lunchtime. And the afternoon brings more leisure — writing postcards, short letters or more-ambitious travel notes, another game of chess maybe, some more photos, idle shopping for the best dates in town (the ones stuffed with almonds or chocolate)…. It’s a magical place where you are free of impatience and even the air is still.

But if you are disciplined enough to break away from the nothingness, there are some sights that should not be missed.

Shali, the ancient fortress built in 1203, reigns supreme in the middle of town. The minaret of a 17th-century mosque is still standing, and the ruins of the Old Town are quite impressive. At night, the entire hill is illuminated, offering a splendid view of the city.

There are two temples of Ammon in Aghurmi, the deserted village three kilometers east of Siwa. First and most important is Alexander’s Ammon Temple of the Oracle, dating to the reign of King Amasis (570-526 B.C.), who is represented on a bas-relief wearing the crown of Lower Egypt. The temple shows a combination of Greek and Egyptian architecture.

At present, the temple is under the care and auspices of German archaeologists who are continuing the excavation started in 1970 by Ahmed Fakhry, an Egyptian archaeologist. Among the main findings are two beautiful Greek steles. One, displayed in the museum of Alexandria, bears the name of Emperor Hadrian. The other, kept at Siwa, praises Ammon.

Umm Ubayda is the second temple dedicated to Ammon, dating from the 30th dynasty (380-343 B.C.). It survived the 1811 earthquake but just barely. Only one wall still stands, beautifully inscribed with four panels of hieroglyphics and colorful images of Egyptian gods — fragments of beauty that give the feeling of a lost ancient treasure.

Celebrations of death and life

Closer to the town center, 20 minutes away by donkey cart and 10 minutes on foot, you find Gebel (Jebel) al Mawta (Mountain of the Dead), the central necropolis of the ancient town. The site dates from the Greco-Roman period, and it has seen some unsettled times. Siwans took shelter in the tombs during the Second World War, as did Libyan refugees fleeing the Italian occupation. Everything worth anything was taken away by tourists and locals alike.

Four tombs have been converted to miniature museums, the most striking being that of Si-Amun, believed to be a local merchant, who is portrayed on rich wall paintings next to his family and Nut, the goddess of the sky. A graceful maple tree completes the image of everlasting serenity.

The other tombs are in relatively poor condition, but I found several mummies sheltered within to be quite impressive. The only mummies I had ever seen before were securely protected under glass at the British Museum and at the Met. These were lying in the open air, shreds of cloth and bones, reminding me of the fragility of life.

The mountain of Jebel Dakhrour, four kilometers east of town, is the site of the Siyaha festival held every year on the full moon after Ramadan. It is a colorful gathering of people and goods, an autumn celebration of life and friendship. When the season lengthens into summer, the entire area becomes a healing ground. People come from afar to be “buried” in the hot sands surrounding the mountain. Believers say that such sand baths, hammam ramal, can cure arthritis, rheumatism and even impotence.

Juba’s nearby spring, also called Cleopatra’s Pool, is said to cool in temperature during the day, but, missing a long T-shirt and shorts, the required swimming attire for women, I was not able to test the claim.

For this December ’06 journey through Egypt I had planned to spend three days in Siwa, but the oasis had a beauty that kept me there for two weeks.

Where to stay

Shali Lodge (phone 011 20 46 460 1299, fax 011 20 46 460 1799 or e-mail info@eqi.com.eg) was my desert dream. It is owned by an Egyptian doctor from Cairo who has both superb taste and extraordinary business sense.

My room cost $50, considered extremely expensive by the locals, but this was one of the best hotels I have ever stayed in.

The lodge is usually booked months in advance — I was lucky to get a room after calling from Alexandria only one day ahead. Credit cards are not accepted; payment is cash only and dollars are preferred.