Rapa Nui: the navel of the world

by Julie Skurdenis

Its first inhabitants called it “Te Pito o Te Henua,” or “The Navel of the World.” Nowadays we call it Rapa Nui, Isla de Pascua or Easter Island. It’s one of the most remote and isolated places on Earth.

Situated in the Pacific Ocean, Easter Island is almost exactly equidistant from South America and Tahiti, each about 2,300 miles away. Although now part of Chile, Easter Island was most probably settled by Polynesians who migrated from the Marquesas sometime in the fourth or fifth centuries A.D. On this small island, they created a society in which individual family units called mata carved out strips of territory beside the sea as well as inland.

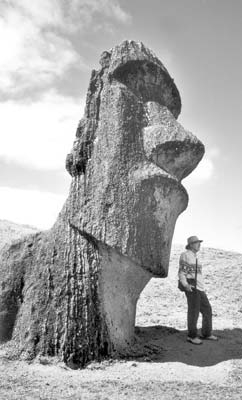

On the land beside the sea, each mata erected an ahu, a ceremonial altar similar to those found on other Polynesian islands. On these altars, as early as the seventh century, moai, stone statues, were erected to honor ancestors. These became progressively larger and larger so that by the 15th century the largest statue stood 32 feet tall and weighed 82 tons.

Then, in the late 17th century, just before Easter Island was “discovered” by Europeans, island society collapsed into chaos and war. The moai were toppled.

I went to Easter Island to see these moai, many now reerected on their ceremonial platforms. For me, it was a return visit. I first saw the statues a dozen years ago on a whirlwind 3-night visit to Easter Island. This time I wanted to share the moai with my husband, Paul, who was making his first visit to the island, as well as spend a few days longer than I did on my first visit.

Tahai — close to town

The most logical place to begin a visit to the moai is at Tahai, located just outside of Hanga Roa, Easter Island’s only town. Tahai is the collective name given to the three ahu located there beside the sea.

In the middle is Ahu Tahai with its solitary weathered moai. To one side is Ahu Vai Uri, lined with five moai. On the other side is Ahu Ko Te Riko, with a moai with inset coral eyes and a topknot made of red sandstone. All the moai stand with their backs to the sea and overlooking what was once a plaza where religious ceremonies were performed.

Twelve miles from Hanga Roa along Easter Island’s southern coast lies Tongariki, where 15 moai — one wearing a topknot — line a 200-foot-long ahu. A tidal wave in 1960 toppled the immense statues, which were finally reerected 10 years ago.

Within sight of Tongariki lies Rano Raraku, the quarry where the moai were dug out of volcanic earth and carved. On the slope leading up to the rim of the extinct volcano, hundreds of moai litter the ground. All were in the process of being carved when, suddenly, work ceased.

Rano Raraku is an extremely atmospheric place. For me, the highlight of a trip to Easter Island is wandering among these half-carved, half-buried statues, some lying face up on the ground, others tilted staring with sightless eyes out to sea, still others in pieces, broken while being moved to their ceremonial platforms.

Moai on the beach

At the far eastern end of Easter Island and along Anakena Beach, fringed by palm trees, lie Ahu Ature Huki — with the solitary moai reerected in 1955 by the Norwegian Thor Heyerdahl in an experiment to see how long it would take (it took 12 islanders 20 days) — and Ahu Nau Nau, with seven moai. The carving on these seven is so clearly incised that you can still make out details of clothing. Four of the moai wear topknots.

Most of the ahu and moai lie along the coast. Ahu Akivi is the exception, lying inland, about six miles from Hanga Roa. Seven moai line the ahu, each supposedly representing the earliest Polynesian explorers who came to Easter Island 1,600 years ago.

If one has time and inclination, there are other ahu scattered around the island with toppled and/or broken statues, giving the visitor an idea of what must have happened just before Europeans arrived.

The ahu and their moai are spectacular, and they alone make the long trip to Easter Island worthwhile, but the island is also rich in petroglyphs. In the southwest corner of the island close to Hanga Roa lies Rano Kau, one of three volcanoes that rose from the sea 2½ million years ago. The lava that flowed from these volcanoes created Easter Island.

Petroglyphs at Orongo

Along the rim of now-extinct Rano Kau is Orongo, a ceremonial village built possibly as early as the 13th century and used until the mid-19th century. More than four dozen oval stone huts stand shoulder to shoulder overlooking the sea.

`

Steps away is Easter Island’s greatest concentration of petroglyphs — hundreds of them — covering the rocks. They represent birds, sea animals and boats, but what appears most frequently are images of the birdman, a cult that developed as a result of the civil unrest that resulted in the destruction of the moai.

Each mata on the island selected a representative to compete in an annual contest to swim out to the tiny islands of Motu Iti and Motu Nui, just offshore, and retrieve a tern’s egg. The first to return with an intact egg would have his chief designated leader for the following year. It was a novel way of restoring order to an island ravaged by war.

Dotted around Easter Island are other, older villages where islanders once lived in houses called hare paenga that resembled inverted boathouses. Now only their elliptical foundations remain, with stone pavements in front and cooking hearths nearby. There are examples of these boathouses at Tahai and at Ahu Te Pau, both north of Hanga Roa.

Easter Island is a very special place. If you’ve traveled this far (travel time from New York can be more than 25 hours), give yourself the gift of enough time not only to visit the archaeological sites in the company of a guide who can explain their significance but to return later on to savor them alone. You are, after all, at the navel of the world, and how many times in life can you claim to have been at the center of it all?

If you go. . .

Our trip to Easter Island in August 2006 was arranged by Latin American Escapes (3209 Esplanade, Ste. 130, El Chico, CA 95973; 800/510-5999 or 530/879-9292, www.latinamericanescapes.com), which specializes in Latin American travel. We’ve traveled with Latin American Escapes to Bolivia, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru and, previously, Chile’s Atacama Desert.

Latin American Escapes arranged our flights, hotel accommodations for five nights at the elegant Plaza San Francisco Hotel in Santiago preceding and following our Easter Island trip, accommodations on Easter island for five nights at the Iorana Hotel, on a cliff overlooking the ocean, and a private guide-driver for four days.

A private trip similar to the one we purchased should cost between $6,000 and $7,000.

We flew LAN Chile (866/435-9526, www.lan.com) between New York’s JFK and Santiago and between Santiago and Easter Island.

A special place for dinner on Easter Island is the quaint French restaurant La Taverne du Pêcheur (phone 100-619), located beside Hanga Roa’s tiny harbor. Dinner for two will cost about $100, including a bottle of Chilean wine. Reservations are essential.