Cemeteries Worth a Visit (this month: Asia, the South Pacific and Northern Africa)

Liz and Jack Kaufman of Lake Quivira, Kansas, wrote, “We have visited cemeteries all around the world. The best ones combine history with beautiful gardens and superb architecture…. We would like to read travelers’ recommendations for cemeteries to visit.”

So we requested that subscribers each name a special, historic or quirky cemetery that they visited outside of the US in the past few years and to tell us what most impressed them about it.

In the last four issues, we printed responses about cemeteries in England, Ireland & Sweden; France; Switzerland, Germany & Italy, and Czech Republic, Romania & Russia. In this issue, the locations featured are in ASIA, the SOUTH PACIFIC and NORTHERN AFRICA. Next month, Latin America.

Marble monuments on manicured lawns are usually intended to glorify the dead for the benefit of the living. Two stark war cemeteries had a very different impact on me.

• In northwestern TURKEY, the Lone Pine Commonwealth Cemetery is located on a plateau on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

On April 25, 1915, an amphibious landing on the peninsula was the start of the Gallipoli Campaign. At the end of the 8-month campaign, more than 8,700 Aussies and 2,700 Kiwis had been killed — many of them teenagers — 472 of whom are in the 1,167 graves at Lone Pine.

I visited Lone Pine in 2001 and was so affected by the horrendous death toll that I returned in 2011. Even worse, Lone Pine is just one of 21 cemeteries for Commonwealth soldiers who died fighting in the Gallipoli campaign.

We should also mourn the more than 80,000 Turks who perished defending their country during battles throughout Gallipoli.

To reach the cemetery, in the Anzac area (around the Sari Bair Range), take the Chunuk Bair road toward Kemalyeri and go 10 kilometers. Lone Pine is on the right. It is a well-known site, so any traveler should be able to get directions once in Turkey. The cemetery is always open.

• The Taukkyan War Cemetery is the final resting place for British Commonwealth soldiers who died in Burma (now MYANMAR) during the Second World War. It’s located off Highway 1 in the township of Mingaladon, 17 kilometers north of Yangon.

Bodies of almost 6,400 soldiers lie under long rows of identical white headstones. They bear heart-rending epitaphs composed by grieving parents half a world away. Memorial pillars display the names of 27,000 more soldiers killed in the sweltering jungle.

The rectilinear grid of graves stands in sharp contrast to the tranquil landscape of cashew nut plantations. In 2004, I stood in the heat and pondered the forces that sent so many to meet their fate in such a remote place. I returned to Myanmar and the Taukkyan cemetery in 2012. It is open 7 a.m.-5 p.m. daily.

Most of the soldiers buried in these two cemeteries, in Turkey and Myanmar, left home with no clear idea of where they were going. Nor did they know the real reasons they were being sent to kill and die while so very, very young.

I’ve seen cemeteries for princes and paupers in more than 100 countries, but cemeteries such as these stand out as testimonials to the madness of war. Some of the visitors who understand the futility that filled these graves will return home and oppose such violence.

Rob Sangster

LaHave, Nova Scotia, Canada

During a visit to SOUTH KOREA in October 2014, my husband, Wayne, and I had the opportunity to visit the only United Nations Cemetery in the world. The United Nations Memorial Cemetery in Korea (93, UN Pyeonghwa-ro, Nam-gu, Busan; travel hotline +82 2 1330, www.unmck.or.kr/eng_index.php) is located in the city of Busan, in the southeast of the country.

The beautiful grounds have 2,300 graves, set out by the nationalities of the buried service members, in 22 sites. In one section, flags fly representing the home countries of the fallen. There are several monuments there, along with an inviting chapel with stained-glass windows. Well-laid-out walkways make it easy to stroll the cemetery and see all the different areas.

The cemetery’s Wall of Remembrance was completed in 2006 and has the names of 40,896 United Nations casualties. Inscribed on 140 marble panels, these include those killed or missing. This wall honors the soldiers from 16 countries who lost their lives in battle during the Korean War, from 1950 to 1953.

This wall has special meaning for Wayne, as he had a childhood friend who enlisted in the army when he was 19 years old. This young man, Fred Harrison, did not return home.

Wayne found Fred’s name engraved on the wall. Seeing it brought back some very poignant memories. One day you’re playing catch in the street and the next day a friend goes to war.

Wayne and I highly recommend visiting this memorial to those who lost their lives in one of our “forgotten” wars.

[The UN Memorial Cemetery is open daily 9 a.m-5 p.m., October-April, and 9-6, May-September. — Editor]

W.H. (Janice) Buxton

Huntington Beach, CA

Far and away, the most moving cemetery that my wife and I have visited is Okunoin Cemetery (550 Ko¯yasan, Ko¯ya, Ito District, Wakayama Prefecture 648-0211, JAPAN; phone +81 736 56 2002).

One of the most significant sites for Japanese Buddhists, Okunoin, located on Kōyasan (Mount Kōya), is the site of Kōbō-Daishi’s mausoleum. Kōbō-Daishi founded Shingon Buddhism in Japan early in the ninth century. Many Buddhists desire to be buried near his mausoleum.

We knew (probably from a guidebook) that the cemetery had lighting, so we walked there on our own one night. Its paths were dimly lighted. The grave markers had phantasmagoric auras under the huge cedar tree trunks.

As I understand, there is a practice of marking certain anniversaries of death with small stone pillars of varying height. This makes each grave marker unique.

Another moving feature of the cemetery is that many statues commemorating unborn children are placed in a stream.

Both because of our night visit and out of traditional respect, we took no photos. Our 2007 visit to the cemetery was so special, we didn’t want to return in the daytime.

J. Curtis Kovacs, Sun City, AZ

The most interesting cemetery I have visited is the Chinese Cemetery in Manila, PHILIPPINES, where I went in May 2014.

Along with the elaborate crypts, many of the gated, incredibly ornate burial vaults contained flushing toilets, showers, family portraits and chandeliers. Several featured second floors, where visitors could enjoy games of mahjong or watch TV.

It was a real trip. There were no entrance fees, but there were guides who would take you around. It was located between Bonifacio and Rizal avenues in the Santa Cruz area of northern Manila.

Sandi Winter, San Diego, CA

My husband and I took a cruise from Singapore to Hong Kong with Azamara Cruises. The ship made a stop in Manila on Dec. 29, 2014, and the next day four of us hired a taxi and visited the Manila American Cemetery & Memorial (McKinley Road, Global City, Taguig, PHILIPPINES; phone +63 11 632 844 0212. In the US, call the American Battle Monuments Commission [Arlington, Virginia] at 703/696-6900, www.abmc.gov).

We asked the driver to remain throughout our 2½-hour visit (he charged us $40). We wished we had allowed for more time.

This 152-acre site is awe-inspiring, really a “must see” in Manila. The reverence with which the dead are remembered, the murals depicting the Pacific Theater battles in great detail, the listings of the soldiers, American and Filipino, on concrete walls by military branch and each by name, including their rank and specialty and hometown, just took my breath away.

Among cemeteries, this is the one containing the largest number of graves of our military dead of World War II, a total of 17,201, most of whom lost their lives in operations in New Guinea and the Philippines.

The chapel, a white masonry building enriched with sculptures and mosaics, stands near the center of the cemetery. In front of it, on a wide terrace, are two large hemicycles with 25 mosaic maps recalling the achievements of the American armed forces in the Pacific, China, India and Burma (Myanmar).

Inscribed on limestone piers within the hemicycles are the Tablets of the Missing, containing 36,285 names. Carved on the floors are the seals of the American states and territories.

My father survived the Battle of Iwo Jima, so to see the details of that campaign on the mural brought goose bumps. My father had shared only a few details; his generation just didn’t speak about the war.

Daily except Dec. 25 and Jan. 1, the cemetery is open to the public from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. A staff member is on duty in the visitor building to answer questions and escort relatives to grave and memorial sites.

Phyllis Bismanovsky

Mountain View, CA

I visited two unique cemeteries in INDONESIA in September 2014.

• Within Lake Toba on the big island of Sumatra, an island called Samosir has the most beautiful tombs. Each family owns their own land in the cemetery, reserved for generations of family burials.

• In Tana Toraja, on the island of Sulawesi, the Torajan people dig graves in cliff walls and rocks because they believe burials should be between Heaven and Earth. A wooden effigy of the person in the grave is carved to guard the grave.

Another Torajan burial place is Ke’te Kesu, where they “bury” their dead by hanging the coffins from the cliff walls.

For a funeral, the Torajan people have an expensive elaborate ceremony celebrating the person who died.

Carolyn Barkley, Austin, TX

In Queenstown on the South Island of NEW ZEALAND in 2010, I had the luxury of time to spend exploring the city. While riding the Skyline Gondola (Brecon St., Queenstown; phone +64 3 441 0101, www.skyline.co.nz/queenstown/gondola) up to a zip-line, I spotted a large, very old and very interesting cemetery, so I made a date with myself to go there the next day.

On a hillside close to the main part of town, Queenstown Cemetery is located on Cemetery Road, next to the Queenstown Lakeview Holiday Park. Many of the graves are very old and, in the manner of the time, give great histories of the persons buried there. Many tombstones have intricate carvings and inscriptions.

I noticed the graves did not all face a set direction, other than those within small groups. I made a note to ask our tour guide the next day. She said it is a tradition of the Anglican church in New Zealand to place the person to face the view he or she wants to see for “eternity.” I then understood that the graves were facing the mountains, the lake or the valley below.

I was drawn by the ages of the tombstones. Many of the people had died in the mid-1800s, with births in the 1700s. It was common for one marker to contain inscriptions for several family members.

But the different styles, the inscriptions and the information contained on the markers were equally fascinating. Many had information about how the persons died.

The cemetery is in current use, so, of course, a visitor should be quiet and respectful. It’s about four blocks up from a main street of Queenstown, and the beauty of New Zealand is all around.

Leeann Moore,

Colorado City, TX

Visiting the North Africa American Cemetery & Memorial (BP 346 Sidi Bou Said, 2026 Tunis, Tunisia; phone 216 71 74 77 67), a military cemetery in Carthage, TUNISIA, was a very emotionally moving experience. I was there on May 10, 2009, while on a Vantage Deluxe World Travel tour, “Tunisia: the Mediterranean & the Sahara.”

Located approximately 10 to 12 miles outside of Tunis, the country’s capital, and five miles from the airport, the cemetery is one of 24 American cemeteries in foreign countries maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission, or ABMC (www.abmc.gov).

The cemetery was established in 1948 and completed in 1960. It covers 27 acres, and its 2,841 graves of Americans who died in WWII are arranged in rows divided into nine sections by broad walkways. At the intersections of the walkways are ornamental fountains.

Along the southeastern section of the cemetery, the 364-foot Wall of the Missing, carved from limestone, lists 3,724 names of those missing in action.

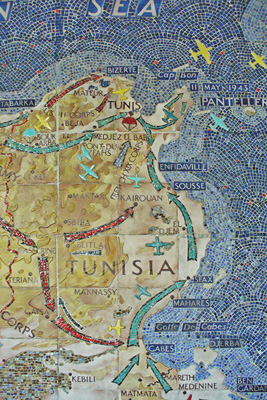

At the end of the walkway are the cemetery’s chapel and its cloister, the Court of Honor. In the courtyard are walls with colorful mosaics and ceramic panels depicting the WWII operations of the American military across North Africa and into the Persian Gulf.

In the chapel’s forecourt stands the Stone of Remembrance, carved from black diorite quarried in Italy. At the stone’s base is an inscription adapted from the Bible’s Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes: “Some there be which have no sepulchre. Their name liveth for evermore.”

On the cloister’s west wall are dedicatory inscriptions in English, French and Arabic.

In addition to the sounds of the splashing fountains and the sounds of nature, the chapel’s bells play patriotic anthems from time to time. Calls to prayer can also be heard from nearby mosques.

The cemetery includes rows of eucalyptus and ornamental Indian laurel fig trees in addition to many other ornamental shrubs and flower gardens.

Since the cemetery actually covers a portion of the ancient city of Carthage, remains of ancient Roman houses and streets can be seen very close by. Other remains of the ancient city are less than a mile away.

Also, hanging in the visitors’ center, there is an ancient Roman floor mosaic. It was originally donated to the American ambassador in 1959 by Tunisia’s President Bourguiba and was later donated to the cemetery.

According to the ABMC website, the cemetery is open to the public 9 a.m.-5 p.m. Monday through Friday except on American and Tunisian holidays. Staff is usually on duty at the visitors’ center to assist people.

While visiting the cemetery was, for me, a very harsh reminder of the horrors of war and the terrible toll it takes in human life, it was gratifying to see that such a magnificent memorial to American service men and women is being so beautifully and carefully maintained on foreign soil.

Also, it was a very educational experience, helping me to learn much more about the role of North Africa in the Second World War.

David J. Patten

Saint Petersburg, FL

Next month, cemeteries worth visiting in Latin America.